The Story of Otakar P. Prachar

I have many collections inside my library. As a certified nerd, it is an impulse of mine to finish any collection I start, and when it comes to books, that often means me chasing down what amount to long lost tomes to finish a collection from before my grandparents were even alive. While this can be frustrating at times, it is also very rewarding. I am happy to be the steward of these texts, such that they continue through time after me.

One of my more elusive collections is that of “Principles of Guided Missiles Design”, the editor of which was Grayson Merrill. The collection starts in 1955, and contains several volumes, all of which are rare and difficult to come by in 2024. However, the most sought-after volume, the Guidance volume by Arthur Locke, was my main priority.

Photo of the Guidance volume of the Principles of Guided Missile Design Series

I was able to get my hands on it in December 2024, and I immediately cataloged and began reading through it. It is always amazing to me how much information can really fit into a well written book, and Guidance does not disappoint. I flipped to a random page around the middle of the book, and found, let’s say, interesting information, but that is a story for another time. Additionally, I noticed a personal stamp on the inside cover.

Photo of the inside cover where Otakar P. Prachar’s personal stamp was placed

This stamp was from one Otakar P. Prachar, and the following is a compilation of my research on his life, career, and ingenuity.

Otakar, who went by Prach, was born in 1912 to a Czech immigrant family in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He grew up in Willow River on a farm, where his father was a beekeeper. The farm was plentiful with wild blueberries, and Otokar’s sister credits the blueberries with his and her longevity.

Photo of Willow River, Minnesota. It is a small town and as of 2010 has a population of 415 people.

Early on, Prach showed that he had a knack for creativity and creation, becoming a skilled woodworker as a child. At the age of 16, he built a fine violin modeled on classical designs. He went on to attend the University of Minnesota, where he graduated with a bachelor’s in engineering and a master’s in physics. In 1941, he would marry Lydia Emma Erickson, a fellow graduate of the university.

Photo of the University of Minnesota, where Prach and his wife Lydia met

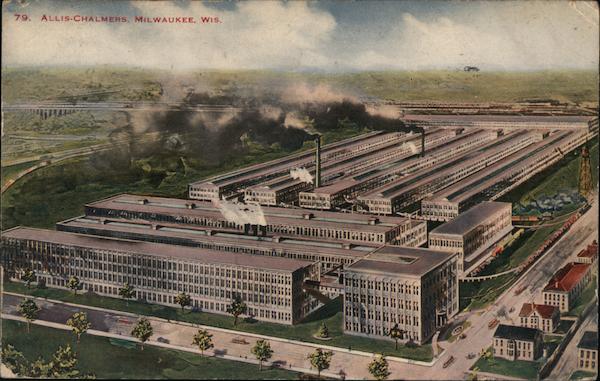

Upon graduation, Prach began his career with Allis-Chalmers in Milwaukee, an American industrial giant who manufactured industrial equipment across many industries. Allis-Chalmers was sold off due to financial struggles in the 1990s

Photo of a postcard featuring the Allis-Chalmers factory in Milwaukee, WI

After a brief stint at Allis-Chalmers, Prach moved to Indianapolis in 1940 where he worked for Allison, a division of General Motors. During World War 2, Prach was involved in modifying the Allison V-1710 engine, which was used extensively in the famed P-51 Mustang and several other fighter planes in service at the time. Prach would go on to patent several engine designs related to the V-1710 and worked on many post-war turbo-jet and other aeronautical engine designs.

Photo of the Allison V-1710 and the P-51 Mustang

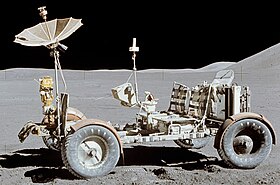

In 1960, Prach and Lydia moved to Santa Barbara, CA after General Motors established a new think tank, the Defense Research Laboratories (later called Delco) in Goleta. While at the DRL, Prach was involved in numerous projects, from military engineering, automotive work and NASA projects. Prach worked on the original designs for collision air bags and worked on the design of the lunar rover. While he was not an avid television fan, he was glued to the TV during the lunar landing in 1969.

Photo of the Lunar Rover and of common automative airbags. Prach had a hand in not only putting humans on the moon, but also in saving millions from crashes

Prach retired from General Motors in 1976 and became involved in a Santa Barbara engineering firm called SeaTek, which designed stabilization systems for offshore oil-drilling platforms. During his retirement, Prach spent most of his time programming computers, working with wood and metal, designing scientific experiments, and reading. He enjoyed showing off his creations to his family and friends and would make fractal designs and science demonstrations. Prach spent a month going down to Hendry’s beach every evening to test his custom program to calculate sunsets. He embraced technology, keeping an iPad by his side and placed amazon orders well into his 100s.

Photo of Hendry’s Beach, AKA Arroyo Burro Beach

Towards the end of his life, his eyesight began to fail him. He didn’t let that stop him, though, and instead of reading, began to listen to books instead, clearing out virtually every audiobook in the public library system. Prach kept himself young by following the antics of his three great-grandchildren. Prach applied the scientific method and his scientific curiosity to his thinking in every domain, whether it be social, political, environmental, etc. Prach learned Russian as an adult so he could read Chekhov and Tolstoy as they were meant to be read. His family was heavily influenced by his message that one’s views can adapt and change by intellectual endeavor and contemplation of all facts instead of simply accepting popular beliefs.

I hope you enjoyed the story!

-Ethan